Your new novel ‘What the Light Reveals’ begins in Melbourne in the 1950s. It deals with father and husband, Conrad, being falsely accused of espionage. The spark for your novel was your uncle’s appearances before the Espionage Royal Commission in 1954-55, based on flimsy evidence, and his later moving to Moscow with your aunt. How much of your uncle and aunt’s story is in ‘What the Light Reveals’?

Transcripts of the Espionage Royal Commission are in the public domain. I was shocked by the bias of the royal commissioners and the Queen’s Council representing the Menzies government. When you consider Vladimir Petrov was paid £5000 (worth around $170,000 today) by our government to defect and hand over documents, any ‘evidence’ or testimony he provides is tainted, to say the least. It worked for Menzies, though, because coming from being extremely unpopular in the polls, he won the election he called late in 1955. McCarthyism was in full swing in the US and here in Australia the conservatives and the media were doing their best to duplicate the recipe. For a modern day equivalent of stereotyping and bigotry, think of our treatment of Muslims living within our shores.

My uncle, Dave Morris, appeared twice before the Espionage Royal Commission, where he was forced to defend himself against the assumption that – as a communist and someone with access to military secrets during the Second World War – he’d passed those secrets to the Russians. Not only was there no evidence to support this claim against him, not a single person from the hundreds called to appear was committed to stand trial in a court of law as a result of the royal commission. Uncle Dave was an idealist, with a strong belief in socialism, but he was also a proud and loyal Australian. Nevertheless, he became unemployable after his hearings, because the Prime Minister was signing letters written by the director general of ASIO, warning each new employer that Dave Morris was a security risk and must be sacked. These letters have been released under Freedom of Information laws. Dave was a highly experienced engineer but lost a string of jobs after a week or two of employment, a pattern that continued for several years.

This is the initial source of isolation the Murphys – my fictional counterparts to the real life Morris family – have to endure, exacerbated by biased media reporting. The level of isolation within community and family I describe in the book is fiction, as is the significant majority of action and plot in Russia. But Dave and Ruby did take their sons to live in Russia.

Importantly too, while in the story older son Alex is adopted and younger son Peter is Ruby and Conrad’s biological son, in real life, both boys are adopted. There’s more dramatic tension in creating this potential source of conflict between the boys.

How important was it for you to focus on each family member’s story?

The one thing all Murphys have in common is membership of their family. Different characters have different views on communism, on the physical and emotional trials of life in Melbourne and Moscow, on their connection to their extended family. But what increasingly tears at the fabric of the Murphy’s bonds within the family unit is not their isolation from Melbourne and its people, or Moscow and its people, but their isolation from each other. The belonging to a tribe, holding an idealistic faith in socialism despite the practicalities of life in the Soviet Union, cause Conrad, Ruby and Alex to confront moral complexities that demand a betrayal to one or more of the tribes they belong to. Ultimately, ‘What the Light Reveals’ is a story about belonging and the best way to convey each character’s inner struggle with these competing loyalties was to show it from multiple points of view.

What kind of research did you do to write a novel partly set in Russia in the 1970s?

Key resources for the Russian setting were my aunt’s book, ‘Between the Lines’ (Bernice Morris) and conversations with my cousin Paul (Alex in the story) about living in Moscow. Two other books were extremely valuable; ‘A Spy in the Archives: A Memoir of Cold War Russia’, by local historian Sheila Fitzpatrick; and ‘Through Dark Days and White Nights: Four Decades Observing a Changing Russia’, by Naomi F Collins, the wife of a US diplomat. Both tell of being a foreigner living in Moscow at the time, with many scenes centred on Moscow State University, where my character Alex was studying. The day-to-day struggles with physical things – shopping queues, the cold weather, the poor condition of their apartment – the awareness of constant informing about you to the KGB by people they studied or worked with, or lived next door to, the anxieties of being under surveillance, the cultural walls that keep foreigners – even socialist true believers – from truly integrating, were gleaned primarily from these four sources. Online libraries of pictorial and video history of Moscow at the time reinforced physical descriptions.

Your first two novels were published just two years apart – ‘Burning Sunday’ in 1999, which was short-listed for the 1999 Age Fiction Prize, and ‘Cutting Through Skin’ in 2001. Then there was a seventeen year gap to this third novel being published. What factors influenced this novel’s long incubation period?

Life happened. After ‘Cutting Through Skin’ it was pretty clear I couldn’t raise a family on the my writing income. I have a PhD in exercise physiology and had worked at Richmond Football Club for seven seasons, running the fitness and nutrition programs for players. Through the 2000s I worked in a start-up company I founded with two friends – an online health and wellbeing service – with a naive notion that if we could make the company valuable then sell it, I’d have the money to support a family while I wrote. That kept me busy for a decade and it mostly worked out as per my plans. But as early as 2004 I was working on a first draft, while working ridiculous hours running my internet start-up.

This novel went through many drafts. What sustained you from one draft to the next, and who helped and influenced the book’s evolution?

Nine drafts, to be precise. Nine! It seems I’m a very slow learner. For many years I was sustained by a pig-headed belief there was an engaging story that could be chiselled from the words I’d written. Antoni Jach’s masterclass VI in 2013 was the first of two important steps in which others helped shape and refine those words. Through Antoni’s guidance and the writing group’s feedback across multiple sessions that stretched the best part of a year, I began to learn what my story was about, what was good and important, and what wasn’t. Then Maria Hyland and Trev Byrne provided macro-appraisals of plot, structure, style and detailed line edits of the final two drafts. I learnt more about how Mick McCoy writes engagingly during those two engagements than in all the preceding years of writing combined. And I don’t mean just for the writing of ‘What the Light Reveals’, but including the first two novels as well.

Do you have any plans for your next writing project?

‘Catch a Panther’ is the next story. The third draft is with my editors – Maria Hyland and Trev Byrne – now. Think Christos Tsiolkas’ ‘Barracuda’ meets David Williamson’s ‘The Club’. Nick Sweeney is a senior coach of an elite football team in the national professional league (the Yarra Panthers in the NFL) and he has bipolar disorder (manic depression). The team’s poor form, the daily media scrutiny, the expectations of the fans and the club, and a league investigation into whether Nick intentionally lost games the previous year (to secure the early picks of the best players in the new season’s draft) are enough to pitch his moods from golden highs to pitch-black lows and back again. Can his team survive, let alone prosper? Can his family? Can he?

What is the best piece of advice you could give to an emerging writer?

Can I offer two?

1/ Seek out detailed feedback from writers / editors. Workshop your story in professionally run writing groups. If you can afford it, employ a professional editor.

2/ When you think you’re finished, put the manuscript in a draw for three months or more; enough time that you can look at your story freshly, as a reader rather than its writer.

|

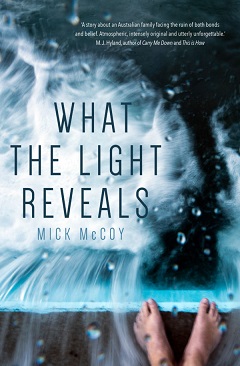

Mick McCoy is the author of ‘Burning Sunday’, shortlisted for the 1999 Age Fiction Prize, and ‘Cutting Through Skin’. He lives in Melbourne, Australia. ‘What the Light Reveals’ is published by Transit Lounge

|

|